If you’ve followed the tech world as it pertains to start-ups and code deployment strategies, one of the

buzzwords you may have heard is “service-oriented architecture” or “SOA”. You can get quite a lot of hits

doing a Google search for those terms - assuming that you ignore all the Sons of Anarchy links, of

course.

Significantly cooler than the SOA I deal with

It’s one of the hot topics nowadays, in line with things like “Agile” and “Hadoop” and “funded”. At

my work, we’re using SOA as well; in fact, I’m at the end of a development cycle where I’m bringing up two

new services. I figured that, at the end of this process, it would be a good time to kinda reflect on what

works about SOA - and what doesn’t.

What’s SOA?

Instead of a typical web application which has the logic all in one place or system (a.k.a. “Monolithic”),

Service-Oriented Architecture splits portions of the application out into separate systems which can be

maintained, developed, improved, and scaled individually. Let me put it in terms of printers. A monolithic

system is like one of those all-in-one printers which can print, scan, fax, copy, read the data cards from

your camera, etc. where an SOA system is like having a printer, a scanner, a fax machine, a copier, and a

card reader. With that analogy in your mind (probably all too vividly), let’s look at the good and bad.

The Good

The main reason SOA gets a lot of traction is because it more or less embraces the Unix philosophy,

specifically “Do one thing and do it well”. If you break an application into its components properly, you

have the ability to optimize each portion of it individually, potentially making the entire system run better

and faster than would be possible if everything was lumped together. For instance, you can get a really good

printer, a really good scanner, etc.

Another benefit is that it’s very easy to upgrade one component in near isolation if you find that it is more

used or more costly than the others. In a monolithic system, it’s very hard to truly isolate one portion of a

system; things are tied together more closely, so what affects one component is more likely to have ripples

throughout. Using the printer corollary, if I want to upgrade my scanner because I suddenly have a need for

higher resolution scans, I’d have to replace the whole unit if I have an all-in-one, but I can replace only

the scanner if it’s separate.

It’s like this, only with code

It’s like this, only with code

A corollary to being able to upgrade one component is that you’re free to use the technology appropriate to

that component rather than being stuck with the same tech stack for everything. This is hugely important

as some types of mini applications can require wildly different types of optimizations. For instance, at my

work, we make a great deal of use of MySQL in our core app because of the large benefits of relational data

models, while in other services we use Cassandra because of its ridiculously fast writes.

One final reason I’ll bring up (there are many more reasons floating around) is that if one service goes down,

it doesn’t mean the whole system goes down. This, of course, depends on how important the broken service is, but

there are many cases where the app can limp along in a degraded state, rather than in a down state. In internet

land, that distinction is pretty important.

The Bad

Usually, you’ll hear all the above things about why SOA is so great. Having worked with SOA and coming from a much

more monolithic background, it’s not all unicorns and rainbows.

First off, having more systems and more servers running those systems means you have a lot more operational

risk involved. I mentioned I’m bringing up two more systems currently; I now have eight points of failure rather

than the two I would have had had I gone with a monolithic system: the monolith (as the services don’t talk

directly to the clients), its storage layer, service 1, its storage layer, service 2, its storage layer, and the

communications system between monolith and service 1 and between service 1 and service 2. Any one of those points

can fail (most of them have for me!), and that will cause issues for this particular feature. Sure, the app was still up, but

the feature I was working on became non-functional. This happened at a far higher rate than the previous feature

I worked on, all on the monolith.

Second, because each system is different, I have to be familiar with all the little moving pieces. Sure, it’s fine

for me having written the features, but now I’m transferring to a different team and thinking about how to transfer

all that knowledge I don’t know I have. This also leads to frustrations when two systems are similar but one is

lacking some component that the other has which does exactly that one thing you need to do right now. It’s great

that you have a template, but now you have to copy it and all the supporting arch for it to the new repo and since

it’s a different system the lib isn’t already shared and etc.

Eh, it’ll do

Eh, it’ll do

Third, different languages leads to people being “jack of all trades, master of none”. This is great… for the

developer. Eventually, unless you’ve got a pro in the language doing reviews and mentoring, you end up with

code which is not nearly as highly optimized as it could be. This usually isn’t critical, but it can have some

pretty astounding effects once you get someone who knows the ins and outs of the system and how to grab more

cycles. As an example, while on Farmville 2, I led the tech side of the operations effort where we halved the number of

servers the code was running on simply by doing incremental optimizations to the code base. None were

massive improvements, but a little here and a little there ended up saving the company tens of thousands of

dollars per month just in operational costs.

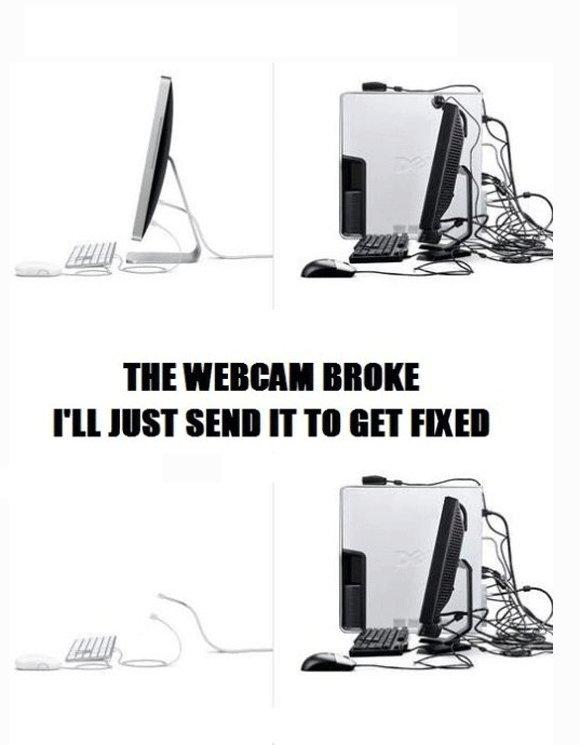

Finally, I think I’ll wrap up the bad with the potential for a developer to be buttonhooked into being the “owner”

of a number of systems. When everything is working well, that’s fine. However, when something breaks, that

developer becomes a bottleneck for getting it fixed. What if the dev is on vacation? What if she quit? What if

he is elbow-deep in building another system on a compressed timeline (which, incidentally, will increment the

number of systems he “owns”) so we have to choose between two business critical systems to work on? I know, things

like this come along all the time in software development. It just has felt to me that it’s more aggravated in

an SOA, probably because of the aforementioned issues, possibly exacerbated by the fact that it’s usually startups

who have few devs that are embracing this strategy. Regardless of the reason, I feel that, unless you are lucky

enough to be able to cross-train your development team effectively, this is going to be a very large pain point.

So what’s the verdict

Toss a coin. It’s very fun building services. It’s very fun putting them together. It’s very powerful and has the

potential to really drive your application into unanticipated levels of performance. But don’t expect it to be

without its issues, and understand that it multiplies complexity by… like 7 or something. That’s a real math

number for you right there.